The butcher, the banker, the costly rules maker

Posted: August 31, 2011

Categories: Food in the News / News from Sustain Ontario / The Meat Press

The next story is ready for consumption! We’re dishing up a second-helping from the perspective of a meat processor encountering Ontario’s regulations. In the coming weeks, I will be bringing perspective from a range of other voices to the table. Look for views from OMAFRA, the Ontario Independent Meat Processors, and more.

Case Study: Cottenie’s Country Fresh Meats

Tony was an A&P meat manager with a dream of owning his own butcher shop. When he got his chance in 2006, Tony and his wife Donna took a leap and started Cottenie’s Country Fresh Meats. Cottenie’s is a butcher shop in Grey-Bruce County that sells direct to customers, restaurants, and through wholesale buyers. Virtually everything that passes through their doors is Ontario raised product. While most of their revenue comes from customer sales, one third was generated from making and wholesaling burger patties to West Grey Premium Beef.

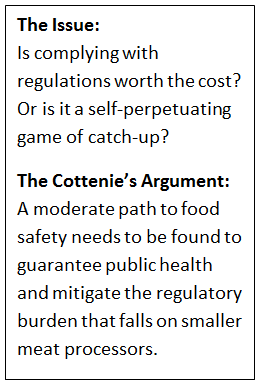

For four years, Cottenie’s operated as a processor and retailer of local meat under the inspection of the municipal public health unit. They never had a problem. In March 2010, Cottenie’s learned that they were now designated as a Free Standing Meat Plant (FSMP), a meat processor other than an abattoir that must be licensed and inspected by OMAFRA. Neither Public Health nor Tony anticipated these changes. Cottenie’s activities did not change, only their designation. OMAFRA was phasing in the enforcement of the Meat Regulation 31/05 (2005) across a growing sphere, which started with bigger – and now smaller – meat processors. If they wanted to continue wholesaling burgers, Cottenie’s needed to become provincially certified. Ever since, it has been a costly game for Tony and Donna to navigate the minefield of regulations and make the upgrades necessary for compliance.

The process felt neither systematic nor comprehensive for Cottenie’s, but set them into action. They called in the provincial inspector to determine what renovations were needed. It wasn’t a modest list. Tony tried to get some of the $25 million in assistance made available by OMAFRA to help processors make necessary upgrades for compliance, but couldn’t access any money. “From the avenues I went through there was nothing available. West Grey tried to help me as well, since they were the ones buying the burgers from us, but they couldn’t get anyone either.”

Without the renovations, Cottenie’s would lose their wholesale burger contract, could not wholesale any other product, and could not undertake any “Category 2” activities, which the meat regulations designate as risky preparations of meat like curing and smoking it or manufacturing ready-to-eat meat products. Tony and Donna decided it was worth the upgrade. Without any financial assistance from OMAFRA, they went to the bank, took out a loan, and undertook a wave of renovations.

“We had to get a new meat saw because the old meat saw was not completely stainless steel, so they wanted it changed. It was $25,000 just for that. Public Health had never had a problem with it before.” They are newly required to pour a costly disinfectant into foot mats to prevent tracking infection through the shop. “For an abattoir where there is a lot of blood, this makes sense. But here there is no need for them here,” Tony argued. The butcher shop was also required to put in a second receiving door to contain infection that could come in off delivery trucks. The double door system would allow arriving product to be inspected in the middle compartment before entering the store. “That was a big joke. The delivery truck has already been inspected. It makes no sense. Every time OMAFRA comes in they want something changed. Something moved, something renovated, something upgraded. It is costing me money every time. I can’t get ahead that way,” Tony anguishes.

His frustration stems from his conviction that no real improvements are being made to their business by these investments. “From a food safety perspective, I don’t feel any better being in compliance with the OMAFRA standards now. We were so good at hygiene and food safety even before.” Tony and Donna believe the risks associated with their operation are less than in larger scale operations or at sites where animals are processed, given that the meat coming through their doors is already dead. “Sure there will be bacteria here like everywhere, but we don’t have the volume that slaughterhouses have for cross contamination. Ninety percent of our meat comes in already boxed and vacuum packed. It goes right into our coolers and then we slice it into steaks and other cuts.”

Tony believes the regulatory burden is incongruent with the scope of their operation. “I would like OMAFRA to be a bit more flexible with certain issues with small butcher shops like us so that we don’t have to follow the stringent rules of slaughter houses. It is really hard to survive with OMAFRA regulations. We’re still trying to recover from the costs, still trying to make a profit. It is going to take a lot to catch up on those renovations.”

When he looks back on their decision to upgrade to provincial inspection, Tony’s conviction wavers on whether it was the right decision. “Donna and I did talk about it and we thought it would be a good money generator. Now that Donna and I got things going how they should be, it’s just gonna take a couple years.” Two to three years by his calculation, before they break even on the renovations. Speculating out loud, he wonders if hindsight wouldn’t compel them to stay municipally certified if they had it all to do over. The kicker that they didn’t anticipate was that in the process of upgrading, they lost their primary wholesale customer. West Grey Premium Beef decided to go elsewhere for burgers, where prices were lower and the new processor was federally inspected. “So we got all this stuff done and no more making burgers.” The patty machine left with the burger contract, and they’re now in the market for a $20,000 machine that will let them continue doing what they invested so many dollars in keeping alive.

To share your thoughts, offer a new perspective, or if you’ve got a lead on a good, used patty machine for Cottenie’s, leave your comments below.

***

Hayley Lapalme is a guest blogger with Sustain Ontario and works with Ontario’s health care sector to help them buy more local, sustainable food. Â You can reach her at hayley[@]sustainontario.ca.

This is a conversation! What do you think?

2 responses to “The butcher, the banker, the costly rules maker”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No surprise. Small guys get squished under a lot of government policy.

I wonder who is the autor of the regulations ? Who is behind OMARA,s name ? I bet U BIG MEAT PRODUSERS !!!Somebody is after small bussiness !

PB.