Making pie, not easy as pie

Posted: August 8, 2011

Categories: News from Sustain Ontario / The Meat Press

Case Study: Forsyth Farm

The Forsyth Farm has been making and selling one hundred homemade meat pies every week for ten years. They raise their own lamb, have it slaughtered, and then process the trimmings into pies. Some pies are sold at the farm gate, but ninety percent are sold wholesale to a distributor. That is, until an Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) noticed a freezer of unlabelled pies waiting to be packaged at the distributor. Under OMAFRA regulations, no meat products made in a municipally inspected site like the Forsyth’s can be processed and sold wholesale. Direct sales to customers or consumption in the home are permitted, but that didn’t prevent $10,000 worth of pies and other Forsyth Farms meat product from being tossed.

Brenda Forsyth had no recourse. “We need regulation, that makes sense to me. But it’s how they handled it that was not okay. To throw it in the garbage was unconscionable!”

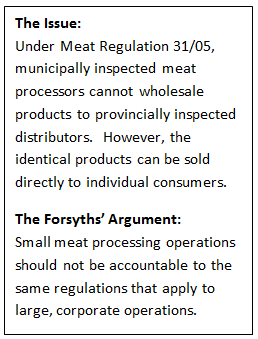

For years, the Forsyth Farm in-house kitchen operation was inspected by Public Health. Unbeknownst to the Forsyths or the local Public Health Unit, their wholesale pie business was absorbed into OMAFRA’s jurisdiction. OMAFRA introduced Ontario Regulation 31/05: The Meat Regulation in 2005, requiring all meat processors selling wholesale to distributors to be provincially inspected. However, the direct farm-gate sales of the same pies could continue uninterrupted under the inspection of Public Health. This allowance assumes that farm-gate customers have assessed and accept the risk of eating their neighbour’s pie, while attempting to protect retail shoppers who wouldn’t have access to the same information.

OMAFRA’s Meat Regulations were rolled out gradually, starting with the largest plants and gradually working through mid-size processors. When they started to bring small facilities under their regulatory umbrella, neither the Public Health unit nor the Forsyths were alerted. “OMAFRA said it was our responsibility to know what the regulations expected of us,” Brenda explained. They had no plan to communicate this and Public Health didn’t know either. So we had catch-up to do.”

Catching up means earning the status of a Free Standing Meat Plant (FSMP), or an operation that is provincially licensed and inspected to process meat for wholesaling. In order to meet the new regulations, the Forsyths would have to renovate their whole operation, move production out of their house, and convert all appliances and surfaces to stainless steel. The renovations are estimated to cost $25,000.

It’s a burden they can’t bear. “There is no economics in it for us to meet their demands when we’re making 100-120 pies a week. I don’t know if I could do it for 500 pies a week. The economics are just not there.” The Forsyths were forced to give up their primary customer and are left with the shell of their original business; a customer base that has shrunk to ten percent. Now they are trying to ramp up these direct sales.

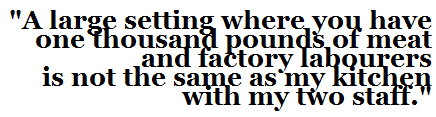

Mrs. Forsyth believes in the food safety regulations but objects to their application. “If I cut a roast in half I am considered like Maple Leaf. I get treated like I am a slaughter plant. A large setting where you have one thousand pounds of meat and factory labourers is not the same as my kitchen with my two staff. We care about every single piece that goes out. Yes, it is easier to clean stainless steel, but it doesn’t mean you can’t clean a kitchen counter.”

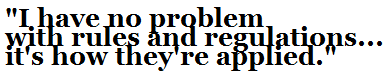

Mrs. Forsyth argues that her name is on the line and that her food safety standards are higher than Maple Leaf’s. She wants some accommodation within the regulations to recognize that small plants like her own don’t need to operate under the same conditions as massive plants. “I would not like to see a lessening of standards,” she says. “I have no problem with rules and regulations because there are always people who will try to do things on the cheap. It’s how they’re applied. There has to be somewhere in the regulations where companies with production under a certain value should be able to produce sustainably in a clean, safe environment.” She wants a different means to the same end.

It is common practice among Canada’s smaller farmers to find additional sources of revenue to supplement their farming incomes. Some have off-farm incomes from secondary jobs and others go the value-added route the Forsyth’s have taken, manufacturing the primary products they raise on the farm into finished consumer products. Â Often, these are the revenues that allow smaller farmers to break even at the end of the year (according to OMAFRA, there are 6,200 farms in Ontario that are operating at a loss and whose annual off-farm revenues yank them out of the red). Finding a way to make this on-farm entrepreneurship food-safe and profitable for farmers could help make small and midsize agriculture more viable. However, the cost of compliance is high for farmers like the Forsyths who want to stay small and process value-added meat products to bolster their earnings.

Two good intentions are on the table: the desire to make a living wage and the interest in public health. Innovation will make these two goals compatible and will make good, safe pie edible for all.

***

Hayley Lapalme is a guest blogger with Sustain Ontario and works with Ontario’s health care sector to help them buy more local, sustainable food. You can reach her at hayley.lapalme[@]gmail.com.

Share your comments below!

Is there is a way to accommodate small, food safe entrepreneurs under OMAFRA’s regulatory umbrella? Should the implications of scale be reevaluated? Would a double-standard be acceptable? Is there potential for more extensive labeling to open new channels of distribution to municipally inspected meat processors? What other solutions are out there?

2 responses to “Making pie, not easy as pie”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

outrageous to toss good food in the dump, shame on you. At least leave the food for the farmer and friends, shame shame.