The Norfolk ALUS Project

Posted: July 20, 2010

Categories: Food in the News / News from Sustain Members

Let Me Tell You About The Birds & The Bees & The Flowers & The Trees

By Bryan Gilvesy

Photography by Laura Berman

Edible Toronto, 2010

I remember the moment it dawned on me. No point in denying it any longer. I was an environmentalist. Along with several other farmers and ranchers from across the country, I was participating in a session examining the future of Canada’s water resources, led by the National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy.

Many comments from farmers centered on the environmental community’s failure to understand the good that many farmers do for environmental stewardship. What I was hearing was a perception that farmers and environmentalists were at odds over how to best deal with Canada’s natural capital – the forests, wetlands and grasslands that form part of our life support system. It all became clear to me then, as I blurted out, “But, I AM an environmentalist, have been all my life. My livelihood depends on it!â€

An uncomfortable silence ensued, but soon a lively discussion started around how we, as farmers and ranchers, had lost the environmental agenda as far as others were concerned despite having been significant contributors to environmental wellness across Canada for generations. How did we as farmers, people who grow food within nature, feel threatened by people interested in protecting our natural capital, when we had the most to lose if nature wasn’t respected?

Ours is a working landscape. In the Carolinian zone of Southern Ontario, stretching roughly from Goderich to Toronto, some 97 percent of the land is privately held and the vast majority stewarded by farmers.

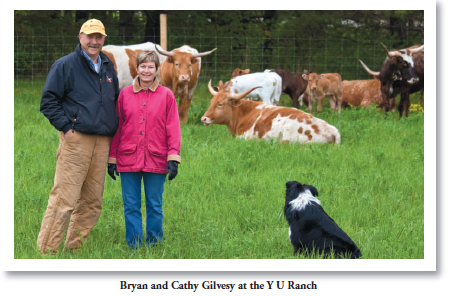

In the heart of this zone, not far from the north shore of Lake Erie, my wife Cathy and I operate the Y U Ranch, a grass-based Texas Longhorn cattle-raising operation. We like to tout our Norfolk County ranch as a model for sustainable agriculture. In fact, the Y U has earned Local Food Plus certification, a gold standard in our province for local, sustainable food combined with a comprehensive, holistic view of the farm. We have deep links to the local food community and are very happy that our operation is driven by the needs of the people who eat our grass-fed beef, not the needs of the next corporation in the “value†chain. We’ve always had a strong stewardship ethic. For years we would race the squirrels to harvest nuts from a grand old American chestnut tree that appeared to be blight resistant, so we could spread the seed of this now-endangered species far and wide across our property.

But life isn’t so simple in the food chain these days and market pressures for low cost food competitive with cheaper offshore products has forced farmers to seek answers in higher productivity – because that’s been the only way to get more reward. In fact, reward for environmental stewardship has turned to disincentive as regulations and market pressures have put a premium on getting maximum productivity out of every acre of tillable land. Today, you see, farmers are only able to generate revenue from the sale of food and fibre, and it would be unreasonable to expect widespread increase in stewardship activities without some connection to farm revenue.

After watching important hedgerows in the county being removed in search of greater productivity, a group of farmers from the Norfolk Federation of Agriculture decided in late 2001 to alter the incentive mechanisms around farming. What resulted was the Norfolk ALUS (Alternative Land Use Services) pilot project, a farmer-led collaborative that seeks to harvest the full basket of value that farms produce. The vision was for farmers to get financial reward for enhancing the natural environment: they would no longer be viewed simply as producers of food and fibre, but also of clean air, clean water, and biodiversity.

As thinking around climate change has evolved, farmers are increasingly being looked to as providers of sustainable climate change solutions. We have the skills (and the soil) to sequester carbon, and ALUS provides the incentives to get multiple co-benefits from the planting of native vegetative cover on farmed lands. Governments, particularly here in Ontario, are beginning to see the additional value that farms can create through the adoption of the Feed-In Tariff program for renewable energy. They have identified a marketplace and a revenue stream by replacing offshore and coal-based power. ALUS is interested in taking the next step: By harnessing carbon and ecological offset dollars, ecological services can be considered part of farm production and green economic activity, just like renewable energy. We can put Ontario in a position to see the environment as an economic driver rather than an economic drag.

Norfolk ALUS is still a pilot project, but now has fifty-five farm families engaged. The project has converted 447 acres of marginal farmland to ecological service, with another fifty families joining in for this planting season in Norfolk County alone. ALUS is part of a national network in Prince Edward Island, Manitoba and Alberta, and is now looking to reward the natural stewardship ethic in more parts of the country.

With cap and trade looming, ALUS began to look to developing carbon markets for long-term funding of the program. The problem is, the sequestration of carbon is too narrow a description of what really goes on when farmers plant native vegetative cover, buffer a watercourse, or restore wetland function. For example, restoration of native tallgrass prairie has benefit for grassland birds, native pollinators and water filtration, on top of the sequestration of carbon. There is a whole range of restored ecological function and ALUS calls this an Ecological Credit. Individuals, governments and companies will have the option of offsetting their carbon footprint, or their ecological footprint, by sourcing Ecological Credits that will be invested in ALUS projects on farmed land.

By now you are wondering, how does this have any benefit for food? The Y U Ranch is an official demonstration site for the ALUS pilot and, upon closer examination, you will realize that ecological benefits can have farm sustainability benefits as well. Initially, 48 acres of tallgrass prairie, a native grassland ecosystem, were planted at the Y U Ranch for grassland bird habitat restoration purposes. These deeprooted plant systems are extremely drought tolerant and consequently serve as dry-season feed for our cattle in late July and August.

By then, birds like the bobolink, meadowlark and wild turkey have finished nesting in the grasses. The grassland restoration has served nature (nesting) and ranching (drought feedstock) at the same time. The cattle that have been raised on such a system have been fed their natural feedstock of grasses throughout the season – providing a leaner, healthier beef product to you, the consumer. And as we ramp up the benefits by adding native flowers that provide nectar for Ontario’s bees, these flowers help grasses grow taller and faster, creating a more productive system based on what nature has to offer.

We’ve also provided housing for some of the grassland birds by erecting forty-two bluebird boxes. We have a whole army of resident bluebirds and tree swallows – all dependent on the grassland – providing insect control services to the cattle. It is sustainable systems like these, whereby the environment experiences a win through carbon storage and ecosystem replacement, that the farmer wins by re-discovering natural solutions, and society – the consumer in particular – wins by having access to healthier food choices produced in a manner that improves the world in which we live.

Exciting new projects are being planted across Norfolk County, with high demand for initiatives that restore wetland function for cleaner water, and a significant new project type we call pollinator habitat. The first pollinator hedgerow was planted as a pilot here at the Y U to address the problem of hedgerows being removed on farms for greater productivity. We are attempting to repurpose what it is a hedgerow does. By planting hedgerows with native Carolinian trees, shrubs and flowers, traditional hedgerow benefits – such as reduced crop transpiration and wind erosion – can be obtained. These systems sequester carbon particularly deep in the soil through the roots. The hedgerow is designed so that there is something in flower throughout the season to provide nectar for many native pollinators.

Our primary focus here is to assist native bees by providing them with a season long food source. These aren’t European honey bees we’re talking about; the almost 1,250 species of native bees and wasps are usually solitary and don’t produce honey, but are a vital link in our support system, providing pollination not just for crops, but for native plants as well. The pollinator hedgerow has numerous functions, not the least of which is free pollination services for much of the food we consume and a reawakening of what nature can offer us as farmers and eaters. This year, Norfolk ALUS has seen a surge in farmers looking to plant more pollinator habitat next to their field crops, a technique that has sustainability written all over it. Remember, though, those incentive dollars through Ecological Credits are the key to converting marginal farmland to ecological function.

The value chain in agricultural is a big topic of discussion today but for the most part, for me the farmer and you the consumer, the value chain is broken. We are disconnected from one another, with the farmer often producing for the needs of the processor or distributor rather than for the consumer, and you grudgingly accepting food as a commodity instead of as one of the most essential components of our health and enjoyment of life. The value chain as it now stands does not reward farmers for the important role they can provide to enhance our natural capital, our life support system, in an age where so much of it is being bulldozed to make room for explosive growth.

Here at the Y U Ranch, we’ve begun in a very small way – together with hundreds of other farmers across the province – to rebuild the food chain by connecting me, the farmer, to you, the consumer. We are defining the role that farmers can play in ecological wellness and human health here in Ontario and are, in the process, defining why you should seek out local, sustainably grown foods. Harvesting the full value of what is produced on Ontario’s farms will unleash the potential of the people and farmlands of rural Ontario and a reconnection to what it is that sustains us all.

Norfolk ALUS Project

www.norfolkalus.com

Y U Ranch

Tillsonburg, Ontario

(519) 842-2597

www.yuranch.com

Bryan Gilvesy is the proprietor of Y U Ranch, chair of the Norfolk ALUS Pilot Project, and co-chair of Sustain Ontario’s steering committee. Y U Ranch is the winner of the 2009 International Texas Longhorn Breeders’ Breeder of the Year Award, a 2008 Canadian Agri-Food Award of Excellence for Environmental Stewardship, a 2007 Premier’s Award For Agri-Food Innovation Excellence, and a 2006 Local Food Hero Award from the Toronto Food Policy Council.