Blog Series Part 2: Food Waste During World War II

Posted: October 5, 2016

Categories: GoodFoodBites / News from Sustain Ontario

Introduction: Why Food Waste?

Globally, around one third of all food produced is lost or wasted. Canadians currently waste $31 billion worth of food every year, with consumers responsible for almost 47% of the value. Why do we throw away so much food? It turns out that cultural practices, habits and institutionalized social norms play a big part in why we waste food.

This is second of a five-part series about food waste in which we explore how Canadians dealt (and deal) with food in the past, present and future.

Food Waste During Wartime

The Second World War saw the national mobilization of military personnel and civilians alike. Food became an integral part of the war effort and was strictly regulated by the Canadian Government. It was through the production, conservation and preparation of food that Canadians on the home front, particularly women, were encouraged to “do their part”. “Food will win the war” was the common slogan. During this era of patriotism and thrift, wasting good food while Canadian soldiers were fighting overseas was seen as a social and moral crime.

Source: Wartime Canada

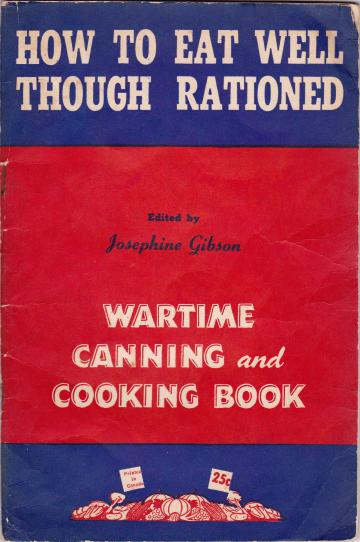

When Britain’s food supplies were cut off, consumers were encouraged to eat foods that no longer had European export markets, such as apples and lobster. This was not the only way that diets changed. When rations were introduced in 1942, staples such as milk, butter, sugar and meat were limited. The resulting change in diets led to the publication of more than 200 wartime cookbooks that demonstrated ways for women to stretch rationed ingredients as far as possible in order to feed their families. Despite this, rationing was not as strict as in war-torn Europe, and Canadian families did not lack for food. In fact, the war actually saw an increase in per capita consumption.

Food conservation skills were given a more profound meaning. The Department of Agriculture promoted home canning, which became a very popular way to preserve fresh produce. Much of this produce was grown in urban victory gardens, which are estimated to have produced 57,000 tonnes of vegetables at their peak in 1944.

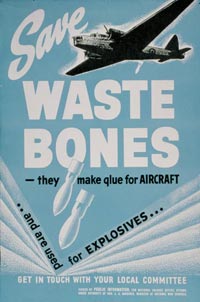

Even ingredients that by today’s standards are considered to be unavoidable waste were recycled. The Salvage Division organized a national campaign to collect materials, including fat and bones. The campaign was directed towards housewives who were encouraged to bring the materials to their local meat dealer. Bones could be used to produce industrial glue, and the glycerin from fat could be used for ammunition. Millions of pounds of fat and bones were collected across the country. The campaign gave Canadians the opportunity to take some part in the war effort, with housewives contributing to munitions exports from their own kitchens.

After the war ended, Canadians remained under the rationing program for a few more years, but soldiers returned home from the war to experience an economic boom. In the postwar consumerist trend that swept North American, veterans not only could support their new families but had access to goods that were more available and affordable than ever before.

Source: Canadian War Museum

Sources:

Wartime Canada, “Food on the Home front During the Second World War”

The Canadian Encyclopedia, “Victory Gardens”

Canadian War Museum, Life on the Homefront: Salvage

Stay tuned for the next chapter in this food waste blog series coming soon: Food Waste in the Post-War Era

See the first post of the series, Food Waste Before WWII.